Thursday, August 26, 2010

Backpack Cooking

Tuesday, August 3, 2010

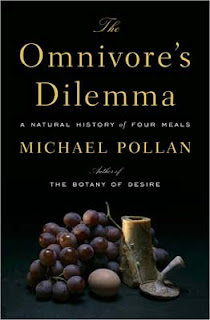

Summer Reads: Omnivore's Dilemma

In reading Omnivore’s Dilemma, I am more fascinated by the convoluting, economically nonsensical and environmentally disastrous policy of industrial farm supports. Yes, that is an opinionated statement. And a sound policy-debate does not start off with such accusations. I understand--all policies are viewed, and defensible, through a perspective. From the industrialist perspective or the US superpower perspective, farm supports uphold a billion dollar food industry. Food security is a good thing, right? But from my perspective, that holds many of the same viewpoints as Pollan’s, farm supports uphold little more than massive corporate profits for a select few at the cost of the small and middle size family farm.

During college, a combination of classes sparked my interest in American farm policy and its effect on agrarian communities internationally. First, there is the economic consideration of property rights and the positive correlation between legally-enforceable land ownership and farm output. This principal is significant in global south development, making the argument for improved legal systems to empower rural farmers, decrease poverty levels. Secondly, enforceable property rights systems include the recognition of indigenous land ownership to prevent squatting, deforestation and environmental degradation. In economic courses, I also studied the effect of farm size on productivity levels. In some cases, such as Vietnam and parts of Northern Africa, communal land plots increase output levels and policymakers argue to recognize these larger cooperative holdings rather than individual land plots when designing a property rights system. Contrastingly, in much of Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa, small farms and single-owner land titles are more productive than communal plots. The factors distinguishing these productivity levels are complex and lie in social, historical, and environmental influences.

Pollan makes the argument that, when measured by amount of food produced per acre, small-scale farming can actually be more productive per acre than big farms (161). If Pollan is only considering the US, I do not dismiss this argument after reading about the massive environmental costs of our industrial food system and the amount of tax payer money that supports it. Vendana Shiva contributes a refreshingly simple expose to the American food systems measure of productivity, revealing it is quite embarrassingly unproductive when considering all costs. But the question of productivity, all inputs and costs included, is key in designing a functioning and enforceable property rights systems in this market-driven world.

“The industrial values of specialization, economies of scale, and mechanization wind up crowding out ecological values such as diversity, complexity, and symbiosis” p. 161 “ Joel believes transparency is a more powerful disinfectant than any regulation or technology. It is a compelling idea.” P. 235 I believe that these critiques of our food system have such profound application to issues confronting our society at large, and the sacrifices that a globalized, high-speed, highly-integrated, market-driven system must make in the way of locality, environmental consciousness economic equality. In a capitalist world, there is no such thing as a free lunch. On a well managed farm, there is such a thing as a free lunch… and breakfast, and dinner.

Other IPE classes, including one focusing on the WTO, sparked my interest in the weight of the industrial food industry in the NAFTA Agreement—and the windfall of the agreement in crippling rural Mexican corn farms due to the wave of cheap, subsidized American corn. Passed in 2000, the NAFTA trade flows of subsidized corn from the US have forced Mexican farmers to migrate to urban centers ripe with crime, drugs and little opportunity. The economic disparity faced by many of these populations has exacerbated the drug wars currently devastating the Juarez region of Mexico. ** Source**

While the NAFTA agreement has been screwing over Mexican farmers since the 2000, Pollan argues that the farm support policies have similarly deteriorated the economic well-being of the American farming communities since the late 1970s, though at a more slower and economically convoluted pace.** For a historical account of US farm policies, see Omnivore’s Dilemma page 44-55.

Farming families are often portrayed as the principal beneficiaries of farm subsidies. Attacking farm subsidies has become politically un-American, synonymous to attacking the people that heroically harvest those amber waves of grain. Pollan introduces an alternative viewpoint; that the farm supports negatively convolute the market for corn by forcing prices lower and production levels higher. In effect, exploiting the farmer by systemically cheapening his commodity. ‘Deficiency payments’ handed out to farmers encourage them to produce as much corn as they can, driving the price of corn in the market even lower. Although the price for corn is plummeting, the only possible way for the farmer to retain the same income level is to grow more corn, flooding the market with more surplus. The margin of profit receivable to the farmer decreases, despite the additional subsidy payments from the government, while the corn coffers of some of the world’s largest food buyers (ADM and Cargill, Cargill=the biggest privately held corporation in the world) are flush with tradable commodities. The American farmer is exploited by these policies, not supported.

In writing this, I feel somewhat guilty of ranting like a conspiracy theorist. How can the story be that simple? Big capitalist took growing food from Farm Belt, turned it into a massive industry that is single handedly responsible for the Mexican Drug Wars, America’s obesity problem, global warming, and complacency and corporate money in politics. Pollan’s book sheds light on another deleterious side of the farm supports previously unknown to me—its screwing over of American farmers for corporate profit.

“But since the hey day of corn prices in the early seventies, farm income has steadily declined along with corn prices, forcing millions of farmers deeper into debt and thousands of them into bankruptcy every week.” P. 53

Quote from an Iowan corn farmer, George Naylor, interviewed by Pollan, “The market is telling me to grow corn and soybeans, period.” As is the government, which calculated his various subsidy payments based on the yield of corn.

This economic policy of paying American corn farmers deficiency payments has created this massive ‘mountain of cheap corn” and economy, society and the environment have adjusted to consume it. P. 62

“Taken together these federal payments account for nearly half the income of the average Iowa corn farmer and represent roughly a quarter of the 19$ billion U.S. tax payers spend each year on payments to farmers.” P. 61

** Here, a point should be made about complacency over time, and its centrality in numbing human aversion to change. Pollan has a great section on this point regarding the slaughter of chickens (p.233). This same notion can be used to describe the reason many of us continue to eat factory-farmed beef. Over time, and when everyone is doing it, the system is habituated and accepted as routine. The usurpation of the American food system to an industrial-complex requires this complacency of the public.

“I wasn’t at it long enough for slaughtering chickens to become routine, but the work did begin to feel mechanical, and that feeling, perhaps more than any other, was disconcerting: how quickly you can get used to anything, especially when the people around you think nothing of it. In a way, the most troubling thing about killing chickens is that after a while it is no longer troubling.”

To be honest, this is why our society will never enact an impactful Climate Change Bill and global warming will be cause the end of humanity on earth. Sorry, dismal. Guess I’m a realist.

In light of Pollan’s account of historical Farm Belt politics, the geographic regionalization of partisan politics today becomes even more transparent. Historically, the Farm Belt of America was the most Republican, most traditional, rural populist core of the country. At the turn of the century, the adversary to the small-scale American farmer was Wall Street, who attempted to drive market efficiency and increase production at the expense of the number of family farms the land could support. As documented by Pollan, Wall Street and the policies of Earl Butz in the post Nixon era succeeded in driving up production levels and forcing farmers off their land. Agribusiness became the new method of production and the American small-scale farmer all but disappeared. This demographic shift cannot be ignored when we consider poverty rates in this country, declining middle class and increasing disparities between the rich and poor. The white, previously middle class farmer has undergone an external systemic shock that has curtailed his ability to produce without massive capital investments in large fertilizers, machinery and acreage. According to Naylor, the farm supports policy since the 1970s has stripped American farm families from their source of income. Whole communities have left the Farm Belt for the big city, office jobs, and economic opportunity. High School counselors advise students with good grades to work hard to get a college education, their ticket out of the economically depressed regions. This leaves only the unmotivated, dim-witted children behind to manage the farm. The miny brain drain oscillating right there within the Mid-West. Motivation for Tea Party activism anyone? And why Tea Party activist come across as so dumb-sounding to left-wing liberals.. because it is all the farmers still stuck in the rural, devote Republican regions of the country that did not succeed in leaving over these past thirty years? P.51

Summer Salads!

Trying to get more leafy greens in my diet, I branched away from the caprese to create the best salad I have ever made. Hands down. I am so proud of this salad, and can’t wait to serve it/eat it again! During a recent trip to Bainbridge Island, I purchased a loaf of Whole Wheat Oat Bread from the Blackbird Bakery. It’s a dense sandwich loaf great for morning toast with a light spread. Even better than that, it’s ideal for homemade croutons. Tossed in olive oil, kosher salt and black pepper, I put one inch cubes of the loaf into the oven on broil for eight min. In the meantime, I cut an apricot and avocado, tossed spinach with olive oil, sprinkled toasted pecans and grated fresh asiago over the salad. Then tossed the hot croutons into the salad (crisp, salty on the outside, soft, chewy on the inside). Finally, I poached an egg and nestled it on the top. The egg yolk added warm richness to the spinach and melded the creamy avocado with the sweet-tart apricot beautifully.

Absolutely, a great salad.

Summer Spinach Salad

One apricot sliced in cubes

Half an avocado, sliced in cubes

Spinach

Grated Asiago

Toasted Pecans

Homemade Croutons

Poached Egg

Olive oil

Kosher Salt

Black Pepper

Sunday, August 1, 2010

Vegetable Garden and BBQ

This Saturday, my roommate and I went to buy the basics for our late summer, early fall vegetable garden. A trip to the Mecca of garden stores seemed in order, with Passion Fruit Iced Teas in hand. We traveled to Molbak's in Woodinville, spending sufficient time exploring the aisles of dense shrubberies, trees and flowering forgery. Then to the seed aisle for our vegetable staples: beets, radishes, wintergreens, broccoli, pumpkin, parsnips, carrots, and a collection for a bad-ass herb garden, Basil Thugs ‘n Harmony. Yep, dorks.

After heading back along Lake City, and feeling the first step of achievement in our anti-industrial, resourcefully sustainable project, we decided to stop for lunch. But not just any lunch, the behemoth beast of BBQ. Rainin Ribs in Lake Forest Park. A place known to marinade, smoke, tare, and sauce up pork, brisket, and chicken like no other. I mean, what more could motivate germinating seeds like a pulled pork sandwich?

We’ll be enjoying our winter greens and home grown squash all winter long. A summer BBQ sandwich slathered in the voo-doo hot sauce needed to fortify us now. The amount of petrol energy and corn-fed piggies we will save with our veggie patch will more than make up for one Brierley Bomber (the special jalapeno-infused pulled pork + hot link sausage sandwich I ordered). It was worth it. No doubt.

In addition to extensive entrees/sandwiches, the place had a great list of sides including fried pickles, fried okra, collard greens, sweet potato fries, rice and beans and more. The homemade hot sauce collection was impressive: Sweet Caribbean, Spicy, Texas Spicy, The Big Red (Ketchup under pseudonym). I’ve decided good lunch places must provide hot sauces/salsa for me to experiment with on every bite. I love hot sauce. We were commenting on the lack of kicking hot in this selection, when the guy came out of the side door with a sauce pan of the voo-doo hot sauce, the realll hot sauce, fresh of the burner. Guess we didn’t look like serious eaters at first glance. Psshht. We told him to dollop it on!

Not an immediate kick, but a slowly rising spice that fills the entire mouth and bite, more than just immediate burn of the tongue and eyes. A real mature champ, a sophisticated sauce I’d say. To finish off my sweet potato fries as a sort of dessert, I mixed the voo-doo with some sweet Caribbean; my sweet and spicy. This is going to be a great vegetable garden.

Blackberries, Apples, Lavender and Rosemary

Compared to the coaxed basil or caged tomato vines in their planter boxes, these wild plants are dominating the summer bounty. I can’t help but be totally impressed by the production of the uncultivated. They are everywhere, like weeds! Massive walls of blackberry bushes line the Burke Gillman Trial and I-5 entrances around the city. Who needs watering from a hose every morning, or snail pellets, we’ve been here for decades doing what we do naturally—Thriving! The faint-hearted gardens are like domesticated house cats compared to these wild cougars of the urban environment.

After finishing Michael Pollan’s book Omnivore’s Dilemma, I was inspired to be more conscientious of where food comes from, and how our industrial/capitalist perspective has distorted the notion of food availability to something processed and purchased rather than, a product of sun, soil and fertilization. As the rogue blackberry bush demonstrates, producing food is not a zero sum enterprise, and certainly not, a negative sum enterprise, like our industrial food system. Our current food system pumps roughly ten units of petroleum energy into the seed production, fertilization, harvest, and transportation for one unit of food (See Alternative Radio’s piece with Vandana Shiva on social justice and development). When done locally, producing food is a positive sum enterprise, in which the energy of the sun produces a unit of food using inputs of water and non-exhausted soil.

In honor of these principals, I decided to put all of this excess sidewalk produce to use. As fallenfruit.org points out, many of the trees in our neighborhoods have been here longer than we have, and will continue to be here once we move on. For me, forging these berries and apples is a reminder of my relation with my local space in comparison to the trees in my neighborhood(my garden will most likely stop being here once I move). Pollan even puts a name to the practice of forging in urban areas:

“The Romans called it usufruct, which the dictionary defines as “the right to enjoy the use and advantage of another’s property short of the destruction or waste of its substance.” P. 398 Check out fallenfruit.org for more on forging neighbor’s fruit.

There are plenty of blackberries in the backyard to eat fresh every morning. With this monster of a bush residing conveniently in my backyard, it is simple enough to walk out to the back for some sun-warmed berries to add to my morning yogurt or oatmeal.

But, I never turn down an excuse to bake, and decided to turn the summer bounty into a sort of celebratory bake-off. Pollan discusses the motivation to transform a bowl of cherries into a galette in his final chapter, A Perfect Meal. He acknowledges that through his forging, hunting, and preserving he learned a great deal about nature’s process of cyclical growth and harvest, why not just eat the cherries fresh on a bowl of ice? But for his dinner party, he explains that cooking is a gesture of gratitude and appreciation for the people you share a meal with. He goes on to argue well-executed and flavorful cooking is a “way to honor the things we are eating, the animals, plants and fungi that have been sacrificed to gratify our needs and desires, as well as the people that produced them.”

“Cooking something thoughtfully is a way to celebrate both that species and our relation to it.” P. 404

With that sentiment in mind, I thought, why of course I must honor this prolific blackberry thicket by adding butter, sugar and a crumbly oat top. DUH. I will enjoy it that much more. But, all sarcasm aside Mr. Pollan, I do agree. One of the reasons I have always been fascinated with baking is for the seemingly simple steps that transform ~ a dozen ingredients into a cohesive, entirely different and enhanced final product. The blackberry’s juice and tart sweetness fuse with the lemon juice and nectarine chunks for a delicious filling under a crumbly oat top. C-E-L-E-B-R-A-T-E. Trust, me this morning when I had a slice of this crumble with my coffee, I appreciated that rogue thicket in the backyard fully; turning the sun and soil into a berry I could then transform into this delicious breakfast. Just think—circle of life (with a final touch by Martha).

Blackberry Nectarine Crumble (Deep Dish)

Bake 375 degrees, 35-45 min.

Crumble Top

Adapted from Martha Stewart’s recipe for a Sour Cherry Pistachio Crisp. I did not have ground pistachios, but this would be a great addition to the next crumble. This recipe for a crumble top is the best I have ever come across, and will use it many more times to come. I will be sure to store this in favorites section.

½ cup chopped unsalted pistachios

½ cup plus two tablespoons all-purpose flour

½ cup rolled oats

¼ tsp baking powder

salt

6 tablespoons unsalted butter, softened

¼ cup granulate sugar

3 tablespoons packed light brown sugar

- Whisk together flour, pistachios, oats, baking powder, salt in a medium bowl. Set aside.

- Put butter, brown and granulated sugar in a bowl and mix at medium speed until creamy.

- Stir flour mixture into butter mixture until just combined. Work mixture through your fingers until it forms coarse crumbs ranging from small peas to gum balls, set aside.

Pie Crust

Adapted from a Patee Brisee Recipe in Martha Stewart Living and California Heritage Cookbook (The Junior League of Pasadena-1976). The California Heritage Cookbook had a great suggestion; after cooking the pie crust for 15 min by itself with foil and rice weights, brush the top of the pie with a lightly whipped egg yolk and cook for two minuets until eggs sets. This prevents the blackberry/nectarine juice (and, trust me, this is a very juicy pie filling) from making the pie crust soggy.

Patte Brisee

Enough for two nine inch single crust-tarts. Originally served with a savory tart.

2 ½ cups all purpose flour, plus more for work surface

1 tsp. salt

1 tsp. sugar

1 cup (2 sticks) chilled, unsalted butter, cut into small pieces

¼ to ½ cup ice water

- Combine flour, salt and sugar. Use a pastry cutter to add butter until mixture resembles coarse meal

- Add ice water until dough just holds together.

- Turn out dough on a lightly floured surface, divide in half and shape into a disk.

- Wrap in plastic wrap and chill at least 1 hour or overnight.

Blackberry-Nectarine Filling

6 chopped nectarines

4-5 cups fresh blackberries

¾ cup sugar

juice of 1 lemon

cinnamon

corn starch (optional)

tapioca balls (optional)

I didn’t just celebrate the berries, but also the crisp, tart green apples covering the branches (and sidewalks!) of some neighboring trees. I decided on one of my mother’s favorites; the apple galette. The name is French prissy (or is it prisee?... as in pate brisee), making this rewardingly simple desert much more elegant.

Using the same basic pie crust recipe, and the CA Hertiage’s tips on using egg to enhance a pie crust, I adapted the apple pie filling from my William and Sonoma Essentials of Baking recipe for Apple Pie.

Apple Galette

Bake 375 for 35 min.

Basic Pie Crust

From California Heritage Cookbook

1 ½ cups flour

½ tsp. salt

6 tablspns firm butter, cut into small pieces

3 tablspns shortening (I substituted butter)

3-6 tblspns ice water

1 egg yolk

Work flour and butter together using pastry cutter until butter is about the size of small peas. Ass the water an quickly work together with your fingers into a smooth ball. Wrap in waxed paper and chill for at least 15 min before rolling

On a lightly floured work surface, roll out into a circle about 1/8 inch thick, 2 inches larger all around a 9 inch pie pan. Fit pastry loosely into the pie pan, then press it lightly into the bottom of the pan, flute and chill for 30 min.

Place a piece of aluminum foil in the pastry shell to form a lining, then fill with dry beans or rice to keep shell from puffing when baked.

Place in preheated 425 degree oven for 15 to 20 min or until the bottom is set and edges lightly browned. Take form oven and lift out the foil and beans. With a pastry brush, coat the shell with lightly beaten egg yolk. The yolk seals the crust and prevents it from soaking up any liquid and becoming soggy. Cool the shell before filing.

I used the remaining egg white brushed over the edges of the galette. It added a pretty sheen and crispy outer texture.

Apple Pie Filling

6 Apples

1 tablespoon fresh lemon juice, strained

2 tablespoons unsalted butter, melted

¼ cup firmly packed brown sugar

1 ½ tsp nutmeg (I substituted cinnamon, a lot of cinnamon)

- Slice apples into ¼ inch slices. I kept the peels on, some suggest peeling the apples prior to slicing.

- In a large bowl, combine the apples, lemon juice, melted butter, brown sugar, cinnanmon. Using a large spoon, stir until blended.

In my celebration of summer’s abundance, I wanted to highlight another plant in nearly every Seattle front yard. Actually two. Two herbs: rosemary and lavender. After walking back home from a morning run, I covertly snapped off some lavender stalks gracing the front entrance to a nearby Mormon Church. The sun and the Later Day Saints will be blessing this cake. Beat that Pillsbury. Briskly turning the corner without looking to see if Joseph Smith was chasing me down, I knelt by a neighbor’s hearty looking rosemary bush for some fresh branches. Just like that I had a bouquet that would add a unique fragrance to a cake. I let these herbs dry for a day before adding them to the cake.

I have wanted to try a savory/sweet olive oil, polenta cake. 101cookbooks highlighted one recently, and I remember some delicious sounding almond versions. Regardless, I have been interested in experimenting with the earthy tones of olive oil and hearty polenta texture in a cake. With that said, this recipe did not exactly hit the note I was looking for. I wanted more cake, this was more like cornbread. I will try the 101cookbook version next time and be sure to get fine grind polenta. Martha Stewart Living had a delicious-sounding version for an Almond-Polenta Cake with almond paste that I would like to try.

Lavender-Rosemary Polenta Cake

Adapted from William and Sonoma’s Essentials of Baking Cookbook.

¾ cup golden raisins (I left these out, the recipes says to soak them in brandy)

¾ cup find grind polenta or cornmeal

1 ¾ cup all-purpose flour

1 ½ tsp baking powder

½ tsp baking soda

¼ tsp salt

1 tblspn orange zest

3 large eggs

½ cup olive oil

¼ cup honey

¾ cup plain yogurt or buttermilk (I used whole milk)

¾ cup toasted pine nuts

1 tablspn dried lavender flowers

1 tblspn finely chopped rosemary

Glaze (I left this out, making the recipe more like a cornbread instead of cake)

¼ cup honey

¼ cup fresh lemon juice, strained

1 tablspn dried lavender flowers

1.Toast pine nuts. Soak raisins in brandy, if using.

2. In a small bowl combine polenta, flour, baking powder, baking soda, salt and lemon zest. Set aside.

2. In a large bowl, whisk eggs until blended, stir in olive oil, honey, and yogurt. Add all but 3 tblspns of the pine nuts (for topping), lavender, rosemary and orange zest.

3. Add dry ingredients to the mixture and stir until just combined. Pour batter into prepared 9 inch spring foam pan (I used a deep dish skillet).

4. Bake for 25-30 min in 350 degree oven

5. Make glaze in small saucepan by combining lemon juice (orange juice), honey, lavender flowers. Bring to a boil over medium heat stirring until sugar is dissolved, then remove from heat and let cool.